Klaus Schwab and the Men Who Molded Him (Part Two)

“When the devil is called the God of this world, it is not because he made it, but because we serve him with our worldliness.” - Thomas Aquinas

Arguably the gravest mistake humanity could make, as we peer into the abyss of a biomedical surveillance state, is confusing those who would implement this psychotic future for some kind of omnipotent, irrepressible force. Yes, Klaus Schwab and his network of World Economic Forum collaborators are no doubt formidable. To a very great degree, they may well constitute the single most broad-reaching coalition of wealth and power ever assembled, but nevertheless, over the course of just the last few years – breakneck speed when taken in terms of civilizational history, slow as molasses if you’re living it – mankind has begun, finally and inexorably, to awaken to the reality of its own enslavement.

The list of jailors is both long and lengthening. Needless to say, aside from the actual architects of the Great Reset, the Jacques Attalis and Yuval Noah Hararis of the world, those most criminally complicit are the presidents, prime ministers, and other assorted political goons who sold their citizens out, first to the Cabal’s dream of a digital aristocracy and then to Big Pharma’s still-ongoing psychological extortion racket. Further down are Schwab’s lesser quislings – the unthinking bureaucrats, the bought-and-paid-for journalists, the apathetic judges, the vapid celebrity mouthpieces, not to mention, the gaggle of feckless, cowardly “medical professionals” who clambered to lend gleeful, ego-inflating validity to the globalist’s pantomime apocalypse.

And as with tyrants past, among these co-conspirators exist no shortage of spiritual leaders. Of course, whatever Schwab’s beliefs in this regard (if indeed, he has any at all), have been utterly eclipsed by his carefully-scripted, heavily-sanitized corporate persona and yet, by the WEF chairman’s own admission (and as increasingly evidenced by the figures attending his summits), it is clear that Klaus considers religion - or, more specifically, religious institutions - as integral to his ambitions of furthering the Great Reset.

About 21 minutes into this self-funded fluff-piece, Klaus can be heard outlining (in tones oddly reminiscent of a job interview) how he was a man of principal - one who stands up for his values, even in the face of censure and rebuke. This he illustrates with an anecdote:

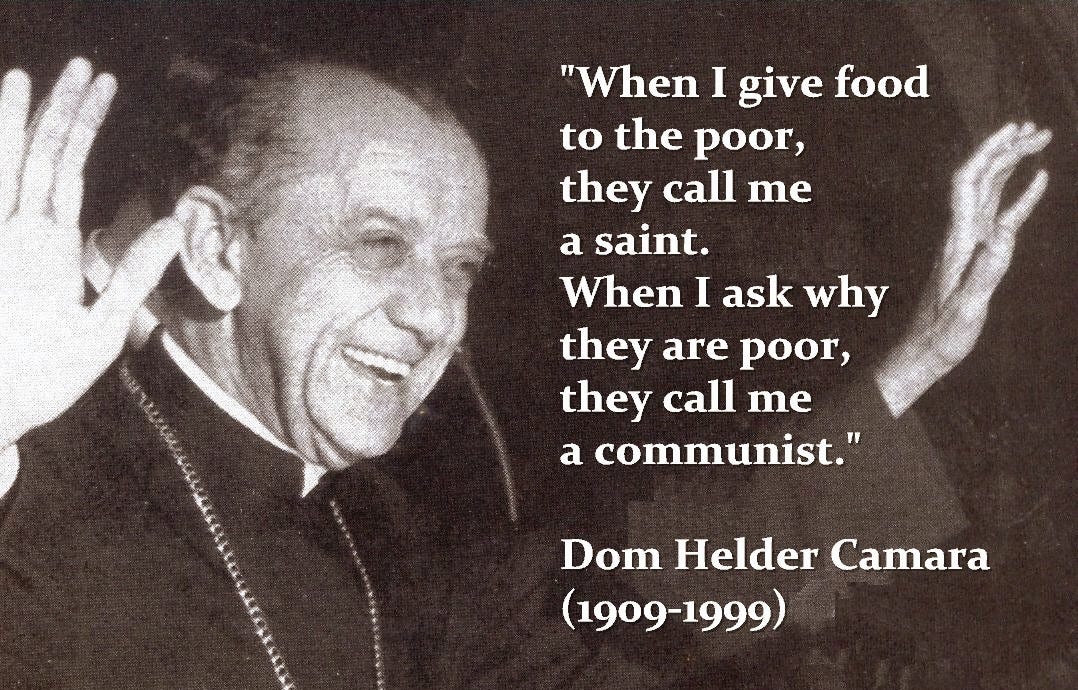

“I give you one example which for me was probably a crucial moment in my life. I traveled for the first time to Brazil, I met a priest who was known at that time as the priest of the poor people. His name was Dom Hélder Câmara.”

Although details of the meeting are virtually nonexistent, it seems certain that Schwab’s trip to South American had been precipitated by the immigration of his parents, themselves following Klaus’s brother Hans, who was managing a branch of the Swiss engineering firm, Escher-Wyss. How the pair’s encounter came about, none but Klaus can say. What we do know, however, is that Câmara, a bishop slight in stature but of immense reputation and presence, showed Schwab around his diocese of Recife, an infamously impoverished shantytown in the north-east of the country. So affected was Schwab by what he claims to have witnessed there, that he was compelled to invite the little clergyman to speak at his convention in Davos. His business associates were less enthused – Câmara was a card-carrying communist, after all. Yet so heavily did the memory of Recife weigh on the conscience of Schwab (as he takes pains to emphasize) that he pushed on regardless, the archbishop’s inclusion so controversial that, for a time, it threatened to jeopardize the still fledgling WEF project.

But while Schwab has been effusive in his praise of the liberal folk hero Dom Hélder is generally depicted as, he - like Klaus’s Nazi father - concealed a history quite at odds with the WEF’s current PR campaign. You see, while still in his mid-twenties, Father Câmara, as he was known at the time, was rapidly rising in the ranks of a clerical far-right movement known as Acao Integralista Brasileira (AIB), later establishing himself on the group’s Supreme Council, as well as in the role of personal secretary to their founder. The organization’s resemblance to European fascist counterparts was not only stark, but intentional. Modelling themselves on Mussolini’s Blackshirts, the AIB boasted their own paramilitary faction, the youthful Câmara so dedicated to their cause that he is said to have wore their distinctive green uniform under his cassock during his ordination. Naturally, this chapter of the bishop’s life has been consistently downplayed by Dom Hélder’s many media apologists (a mere “youthful folly”, according to The Guardian) but at the time, his association with los Integralistas was deemed distasteful enough for the Holy See to deny the Archbishop of Rio di Janeiro’s request to make Câmara an auxiliary.

By the end of the war and for reasons which remain elusive, Dom Hélder had somehow managed to transition from the shaved-head-and-laced-up-boots fascism of the AIB to Assistant General of the Brazilian Catholic Action, whose youth wing, the JUC, were known as vigorously outspoken supporters of Castro’s 1959 Revolution. That said, so too should it be noted that the group was comparatively moderate for the era, at least among the myriad of socialist movements proliferating throughout Brazil, and yet, during the years Câmara was a member, the JUC continued to tumble evermore leftward, eventually becoming so indistinguishable from the Brazilian Communist Party that they were voluntarily absorbed into it.

Having shed his former fascistic credo in favor of a more professionally advantageous progressivism, Dom Hélder soon found himself being embraced by the upper echelons of the church. This would culminate in 1964 when he was appointed Archbishop of Olinda and Recife - by far his biggest ecclesiastical accomplishment to date. However, on a more political level, his prospects looked bleak. That same year, Brazil was swept by an American-backed military coup orchestrated to unseat President João Goulart, whose extensive land reforms and huge tax increases had earned the applause of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Nikita Khrushchev, Chairman Mao, and so often their radical cohort, Dom Hélder Câmara.

Confronted by a regime starkly at odds with his worldview, Câmara did not allow the responsibilities of bishopry to long distract from his activism. In fact, this period was to mark the most politically consequential of his life when just the following year, while attending the Second Vatican Council, he and a cadre of forty-one other ultra-modernist bishops gathered in the Catacombs of Domitilla beneath the Roman countryside (and behind a fig leaf of humanitarianism) in order to pledge themselves to nothing less than the ideological overhaul of the Catholic Church. This they intended to do, not by re-orientating its mission toward truth, forgiveness, compassion, humility, honesty, or any other virtues espoused by Christ, but rather, by aiming its focus solely and exclusively on the treatment of the poor – or, more skeptically, on the eradication of wealth. “The Pact of the Catacombs”, as it has since come to be referred, is as close to undiluted theological Marxism as any mainline Christian document has ventured, the most illustrative passage reading:

“We shall do everything possible to ensure that the leaders of our governments and public services adopt and put into practice the laws, structures and social institutions that are necessary for justice, equality and the harmonious and complete development of the whole human being and of all human beings and thereby for the coming of a new social order worthy of human children and children of God.”

The pact remains the apex of Dom Hélder’s notoriety on the international stage, yet within his native Brazil, the bishop is still better remembered as one of the key players in the fomenting of an altogether more literal revolution. In 1968, the nation’s media got hold of a document allegedly written by a Belgian priest by the name of Joseph Comblin. Prepared in conjunction with the Archbishop, it advocated, in the most unequivocal terms, for the communist overthrow of Brazil, the accomplices even going so far as to provide a blueprint. But theirs was not the Christianity-centered society described in Pact of the Catacombs; this was an uprising all but indistinguishable from its more secular predecessors, its manifesto every bit as brutish and oppressive:

“Social reforms will not be made through persuasion, nor through platonic discussions in congress. How will these reformers be installed? It is by a process of force... the power will have to be authoritarian and dictatorial... the power must neutralize the forces that resist: it will neutralize the armed forces if they are conservative; it will have to control radio, TV, the press, and other media of communication and censor the destructive and reactionary criticisms... In any case, it will be necessary to organize a system of repression...”

The “Comblin Document” would prove to be the catalyst for a root-and-branch recalibration of the Catholic Church’s position within a turbulent Brazil, its co-author’s refusal to distance himself from the sentiments only further solidifying his reputation as the “Bishop of the Favelas.” This was one of many such epithets Câmara would accumulate over the course of his career. An outspoken leftist firebrand, reviled and venerated in equal measure, these ran from the quasi-messianic “Rebel Saint” to the markedly less reverential “Castro in a Cassock” - his moniker of “The Red Bishop” that which Dom Hélder is most strongly associated with today. He earned the title during a 1969 visit to New York, his speech to the Catholic Inter-American Cooperation Program replete with the now characteristic condemnations US foreign policy, reiterated support for the Soviets’ “anti-imperialism”, as well as demands that concessions be made to Castro and Mao, dictators who were themselves in the process of either violently seizing or brutally solidifying their power.

Given the fervor and frankness of Dom Hélder’s leftism, it can hardly be surprising, at least to those familiar with political Catholicism, that Câmara remained, right up until his death, an adherent of a doctrine known as “Liberation Theology”. This nakedly Marxist interpretation of the Bible had proved especially virulent in South America, merging as it did, two ideologies which had long coexisted. The “liberation” these priests spoke of bore scant resemblance to the teachings of Jesus. Instead, their central assertion that “God loves the poor preferentially” had far more in common with the three-word slogans emanating from the left-wing guerilla groups that pervaded much of the South American countryside, insurgents in Nicaragua among the first to recognize the tactical utility of Liberation Theology. Conscripting amenable clergymen, they used its reasoning to legitimize in the eyes of their Catholic congregation violence against the dynastic Somoza dictatorship, Dom Hélder falling well short of condemning the practice:

“I respect a lot priests with rifles on their shoulders; I never said that to use weapons against an oppressor is immoral or anti-Christian. But that’s not my choice, not my road, not my way to apply the Gospels.”

It was amid such an atmosphere (Câmara had just published Spiral of Violence, in part his response to America’s involvement in the Vietnam War) that the elfin bishop was at last to cross paths with a young Klaus Schwab. Vexingly, we can never know how sincerely the emerging business tycoon was affected by the poverty which Dom Hélder showed him (as noted in the first part of this series, Klaus’s childhood had been steeped in human suffering) or whether he simply regarded Câmara as a prospective ally toward expanding the reach of his European Management Symposium, as the World Economic Forum was then known. Either way, as he recounts in the earlier video, Schwab felt ethically-bound to weather the disapproval of his peers to bring the divisive bishop to Davos, where, according to the WEF’s own propaganda, he delivered as speech that was both “well received” and “provocative yet vital”.

This was the beginning of a relationship – ostensibly, a spiritual mentorship – which would endure the rest of Câmara’s life. Once more, the observer is left to speculate on the nature of their correspondence. Was Klaus Schwab, as unfathomable as it may seem, acting out of some truly philanthropic or even moral compulsion? Did he, as several dissenting voices within the church have argued, instead view the rabble-rousing Brazilian predominantly a means of infiltrating another pillar of western civilization? Was Dom Hélder’s interest really any less self-serving? The Red Bishop, as his numerous biographies always keenly recount, was a man who endeavored to attend to the more hands-on needs of his flock and yet, it does not require a particularly cynical mind to suspect that he, like Schwab, was merely using the other as a means of forwarding his own purely political agenda.

It hardly seems necessary to state which camp your humble narrator fall onto. After all, while each figures came from quite disparate worlds - Schwab forged in the post-WWII business boom, Câmara in the slums and seminaries of Brazil - one need squint only slightly in order to see how both men are motivated by much the same objectives. Although Dom Hélder might once have called for the abolition of private property in the name of Christian kindness and the left’s ever-amorphous notion of “The People”, Schwab’s MSM enablers emit much much the same rallying cry, albeit on the grounds of “climate change,” “fairness” and “sustainability”.

This is far from the men’s only affinity. When it came to the issues of divorce and contraception, few Catholic leaders have exhibited the same laissez faire attitude as Dom Hélder - an attitude eminently compatible with the globalist plan to undermine the family and ultimately, depopulate the planet. Even on the hyper-futuristic issue of transhumanism do the pair find accord. It might almost be said that Archbishop Câmara, sworn to a life of pious austerity, proved himself far more forward-thinking than the mega-wealthy, gadgets-and-gizmo-obsessed Schwab, remarking at a 1965 conference of Council Fathers:

“I believe that man will artificially create life, and will arrive at the resurrection of the dead and (…) will achieve miraculous results of reinvigoration in male patients through the grafting of monkey’s genital glands.”

To a large extent, Hélder Câmara was also ahead of Schwab in calling for a Great Reset. That, after all, is precisely what the Pact of the Catacombs represented and certainly, if Catholicism is to survive in a post-Fourth Industrial Revolution world, it is in this WEF-compliant form which it will do so. The same goes for all human religion. One need only pay attention to the growing number of rabbis, gurus, imams, and even shamans recruited by Schwab to realize that each, despite the myriad of traditions from which they originate, all tacitly or explicitly comport to the globalist’s overarching mission:

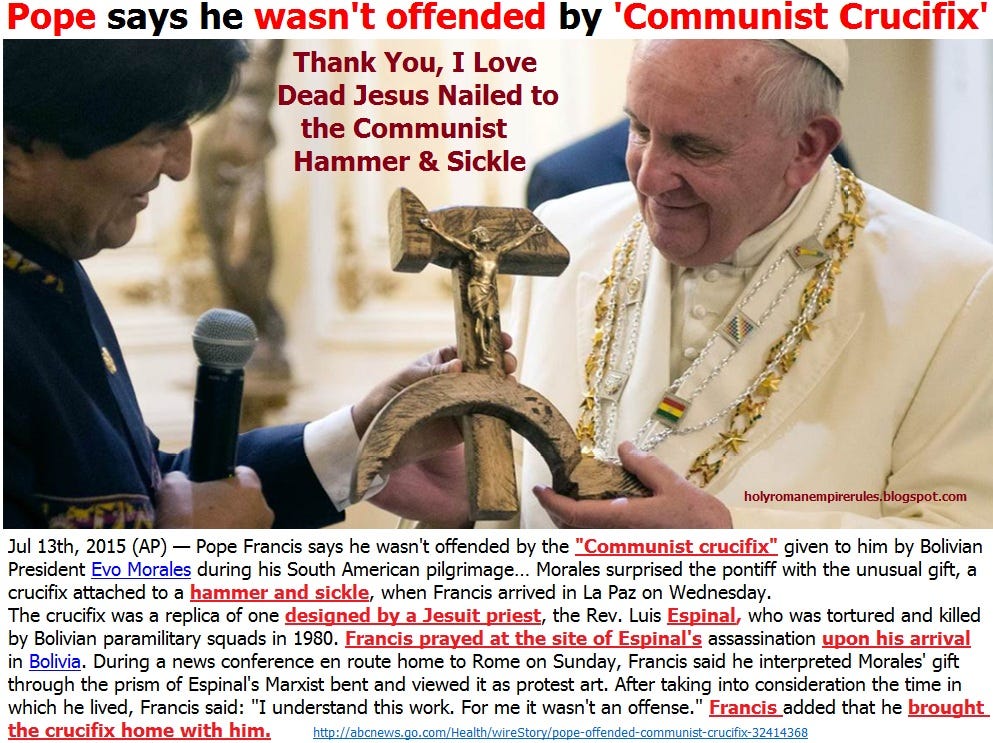

And of all his legions of holy men, none has been more crucial to shepherding in Schwab’s New World Order than Pope Francis. Under the pontificates of John Paul and Benedict, talk of the The Pact of the Catacombs diminished as a guidestone for the Holy See. However, in the years since Francis’s ordination (himself an avowed liberation theologian), its sentiments have not only been more frequently repeated, but repeated right down to the phrasing.

“It was forgotten,” Cardinal Walter Kasper said of the Catacombs Pact. “But now he [Pope Francis] brings it back. … His program is to a high degree what the Catacomb Pact was.”

Massimo Faggioli, a professor of church history at the University of St. Thomas, agrees: “With Pope Francis, you cannot ignore the Catacomb Pact. It’s a key to understanding him, so it’s no mystery that it has come back to us today.”

There are even some suggestions, scattered haphazardly about the internet, that early in his career, Francis had once studied under the tutelage of Câmara, but regardless of the veracity of this claim, what remains unambiguous is the fact that the Pope holds Dom Hélder in peerlessly high regard. Almost immediately after his ordination, Francis described the archbishop as integral the “journey of the Church in Brazil” while more recently, he has made allusions toward beatification (itself a step on the path toward sainthood) – this just one of the many controversial proclamations Francis has made during his relentlessly polemic tenure.

As many within the church had warned, his papacy has overseen numerous cultural and spiritual shifts which many Catholics consider antithetical to their faith. This goes much further than just contraception and divorce. Like his ideological progenitor, Pope Francis has reiterated claims of Christ’s supposed preference for the poor - his support for Black Lives Matter, the LGBT Alliance, and mass immigration little more than a modern reimagining of this old leftist dichotomy. The Supreme Pontiff has also been vocal on matters of environmentalism, Schwab seeing so many parallels with his old mentor that in 2014 - some thirty years after extending the same invitation to Câmara - he welcomed Francis to his ultra-exclusive, ultra-influential retreat high in the Swiss Alps. Since then, the Pope has gone on to become an officially-recognized “World Economic Forum Contributor,” signing off on a variety of aspect to their agenda, the most notable of which a 43,000-word-long encyclical letter approving the WEF’s response to the Covid pandemic.

In other words, Francis was throwing his name – and by extension, his church – behind the Great Reset. The significance of this can scarcely be overstated. While the present Pope may provoke more dissent among rank-and-file clergy than a vast majority of his predecessors, his word nonetheless carries a level of devotion far beyond any of the other world leaders, financiers, or showbiz personalities ushered into Davos’ inner circle. Indeed, in the eyes of his followers, this is nothing less than the word of God - just the kind of endorsement the WEF are desperate to secure as they seek to further penetrate the markets of Africa and South America. For many in these continents and throughout the world, Francis’s allyship provides Schwab the moral legitimacy to push forward with his plans for a global, technocratic caste system and yet it seems unlikely this could ever have been achieved had it not been for the afternoon he spent wandering the slums of Recife accompanied by a five-foot-two-inch giant by the name of Dom Hélder Câmara.

*** Throughout this article, I have linked to numerous materials referenced in its creation. However, it should be noted that it was a piece by Winston Smith over at Escaping Mass Psychosis who first alerted me to the relationship between Klaus Schwab and Hélder Câmara, and thus gave me the idea for this series. His work is exceptional and you should assuredly check it out. ***

Crypto Donations:

Bitcoin: 1MHzr38VAc3g5cucBGiT8axXkiamSAkEkZ

Ethereum: 0x9c79B04e56Ef1B85f148CaD9F4dBD4285b2f9E69

It all comes down to the basic morality and who we are fundamentally as male and female. Men have duties and obligations, and women have their duties and obligations. Marriage is only between one man and one woman for the purpose of sex and having children. The husband, wife and children all have purpose and meaning in a family, and this is how society and civilization is formed. It is fundamentally Christian morality. All laws are then made to protect the fundamental unit of society - marriage and children - so that men, women and children are provided the necessary safety for their growth and happiness. It’s not complicated.

Only hard-core Marxist-Leninist-Maoists and Trotskyites might truly believe that Fascists are "far-right wing." Mussolini and Giovanni Gentile believed man's duty to society, the Nation, superseded duty to God, self or others. Man's worth was only measured in his contribution to the Nation (not country, which they viewed as separate). They actually considered their movement as "spiritual" and, as in other socialist-based movements, were atheistical. My view of the Italian Fascist State as Mussolini, especially, viewed it was it represented the rebirth of the Roman Empire, which is one reason he chose the Fasces, which originated with the Etruscans, as the symbol of their movement. I think they both viewed socialism with disdain because as Marx taught it, the system had no "state" but was rather a kind of boundless (globalist) movement that was led by soviets (councils), the idea of which they actually expanded and formalized into their three-prong absolutist totalitarianism by committee.