Klaus Schwab and the Men Who Molded Him (Part Four)

“Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.” - Fyodor Dostoevsky

The most recent meeting of the World Economic Forum, held as always amid the ultra-exclusive chalets and bubbling hottubs of Davos, must surely constitute the single most divisive gathering of individuals ever assembled. To MSM viewers, this congregation – comprised of politicians such as Al Gore, John Kerry, and Volodymyr Zelensky; corporate interests like Google, BlackRock, and AstraZeneca, as well as the alleged philanthropy of Bill Gates and George Soros – represents nothing less than mission HQ in humanity’s ongoing fight against the evils of Covid, Climate Change, and Putin.

To those who’ve actually been paying attention on the other hand, these crises, all carefully curated, all suspiciously well-timed, are but cover stories for the Liberal World Order’s true objective: the establishment of their global digital caste system. Omitted, after all, from the media’s unerringly obsequious coverage, was the applause reserved for J. Michael Evans, president of the Alibaba Group (a Chinese technological giant central to the country’s emerging social credit system) who boasted of his company’s capacity to track users’ “carbon footprint”, collecting data right down to the most intimate aspects of their lives. So too did CNN, The New York Times and the rest of the corporate PR machine fail to mention remarks made by Albert Bourla – the Pfizer CEO practically purring over the compliance his new ingestible microchip would elicit. But not one to be upstaged at his own slumber party, it was Klaus Schwab himself who offered the symposium’s most memorable address, the host’s characteristically chilling rhetoric leaving little doubt as to the kind of warped, egomaniacal agenda we are dealing with:

For those readers disinclined to listen to anymore of Schwab’s despotic bloviating (a sentiment which, after three prior entries in this series, I am very much sympathetic to), please allow me to select the most illustrative passage:

“The future is not just happening. The future is built by us, by a powerful community such as you here in this room."

To borrow from the language of leftists, this is as blatant a “dog whistle” as it’s possible to get. Downplayed by those programed to do so and roundly ignored by the media he and his ilk control, this statement (alongside many others like it) is intended as an invitation – some might even call it Schwab’s rallying cry – for the world’s most powerful individuals and entities to join him in securing permanent, incontestable dominion over the rest of us. This does not even require an ear all that attuned to globalist doublespeak to notice and yet, despite the scale of the civilizational changes Schwab is proposing, still there appear few observers (and virtually no journalists) who have sincerely sought to distinguish the mind and motivations behind them.

Throughout the course of this series, I have attempted to address this collective blind spot by piecing together an image of the man through first examining those known to have influenced him. In parts one and two, I focused on Klaus’s Nazi-collaborating father as well as his self-described “spiritual mentor”, while in the previous installment, I turned to Henry Kissinger, Schwab’s professor at Harvard and a man who would usher Klaus into the world of Anglo-American elites. These shadowy figures evidently saw potential in the young German. Through him, they recognized an opportunity to extend and tighten their influence over Europe; however, this ambition might have come to nothing had it not been for someone who preceded Greta Thunberg, Pope Francis, and Leonardo DiCaprio onto the Davos stage, becoming in the process, the World Economic Forum’s first keynote speaker.

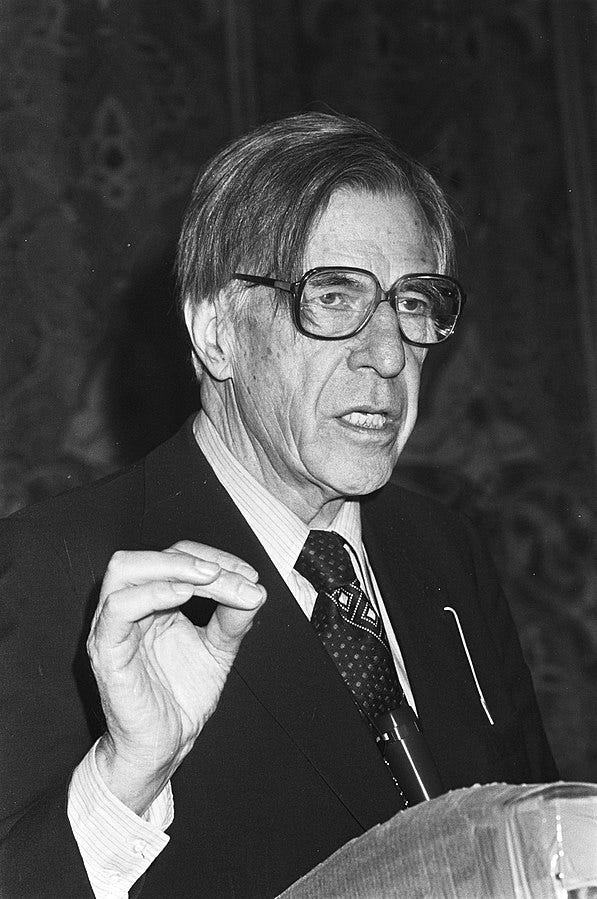

John Kenneth Galbraith – a man who would become one of the most influential economists of all time, and perhaps the most noteworthy disciple of John Maynard Keynes – was born in the small hamlet of Iona Station in Ontario, Canada. The year was 1908. His father, both a farmer and a schoolteacher, was heavily involved in local politics, acting as an official for the Liberal Party. Aside from the death of his mother when Galbraith was just fourteen years old (he had by now fully adopted the moniker of Ken) little has been written of his formative years. Nevertheless, what we do know is that after completing a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture from the Ontario Agricultural College, Galbraith would go on to enroll in his first “real” economics course at UC Berkeley, joining Harvard as an instructor upon graduation.

Galbraith became a naturalized US citizen not long afterward, although this was quickly overshadowed by his entanglement in ‘the Sweezy-Walsh affair’ – a scandal in which two pointedly left-wing professors were dismissed for what were perceived to be purely political reasons. Quite what Galbraith’s involvement looked like is not easy to discern, yet what remains clear is that Harvard deemed it contentious enough that, by the time he was due to have his contract renewed, the college neglected to do so.

This prompted the newly minted, freshly unemployed American to take up a post at Princeton. Here, Galbraith began to establish his first substantial connections to the political arena – connections which would lead to his membership of a panel set up by the FDR administration to investigate potential implications of the New Deal. These ties would deepen further in 1940 when, upon France’s capitulation to the Nazis, he was asked to join the staff of the National Defense Advisory Committee, this just one of several government-run policy institutes Galbraith would participate in prior to acquiescing, in 1943, to Fortune magazine’s requests that he write for them.

The publication had been aggressively pursuing Galbraith for quite some time. It was immediately clear why. Blessed with a rapier wit and prodigious literary talent, Galbraith’s column would soon prove among the magazine’s most popular (even if, in the view of certain contemporaries, this had more to do with the quality of his prose rather than any profound economic insight). The position seemed almost tailormade for Galbraith, well-paid and without the pressures of politics, however, in 1945 and with the German Wehrmacht weakening, he was to undergo not one but two abrupt shifts in career direction.

The first came when he was sent to London as part of a team tasked with evaluating the economic impact of Allied bombing campaigns. At this stage, German surrender appeared imminent and sure enough, by the time his delegation arrived in the country, Galbraith’s assignment had changed once more. Having served as both Hitler’s chief architect as well as Minister for Armaments and War Production, the conviction of Albert Speer was among those the Allies were most eager to secure. And ultimately, they did, Galbraith’s week-long interrogation of the Nazi war criminal a far cry from the policy-suggesting statistics and price projections he must surely have been expecting.

For the next several years, Galbraith would bounce between Washington DC and Fortune magazine – serving on a variety of government think-tanks, working as a speech writer, as well as establishing the prominent liberal advocacy group Americans for Democratic Action – before making his way back to academia in 1948, via an offer to teach economics at Harvard. His return was not universally celebrated. Several senior figures within the department were vehemently opposed to the brand of Keynesian economics on which Galbraith had built his reputation, so much so that they took the virtually unprecedented step of blocking his appointment. But neither was Galbraith bereft of supporters. Indeed, such a fan of his work was Harvard’s president James B. Conant that he threatened to resign unless the naysayers backed down, Galbraith’s subsequent tenure at the college providing him the time to begin work on his first major bestseller, American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power.

The book’s principal assertion was that the American economy could no longer claim to be the competition-based model it was conceived as, primarily due to the fact that large corporations had swallowed up such vast swathes of the market. Fortunately, Galbraith claimed, this dominance was kept in check by the influence of trade unions which ensured economic power centers were widely enough distributed to produce a (broadly) harmonious system. This theory, needless to say, was bitterly contested by many of his peers, although among the public at large, Galbraith’s ideas were to once again find favor.

But however impactful American Capitalism was to prove, it was not until 1958 and the release of The Affluent Society that Galbraith found himself fully catapulted into public consciousness. In this, the author bemoaned, as so many of a left-wing persuasion do, the private sector’s invention and efficiency when set against the comparative mediocrity, listlessness, and often outright incompetence exhibited within the public sector. America was well primed for such a viewpoint. At the time of publication, the US was still experiencing, amid all the Cold War tensions, a period of unprecedented economic growth. Between 1940 and 1965, the average household income grew from about $2,200 a year to just under $8,000 which, when adjusted for inflation, constituted a trebling of household income. This newfound prosperity brought with it a dramatic shift in consumer spending patterns, alongside the reemergence of “conspicuous consumption.” This term had first been coined by Norwegian-American economist Thorstein Veblen in order to explain the tendency of individuals to acquire luxury items as a route toward social status, Galbraith contending that a major increase in public spending, especially in the areas of schools, parks, hospitals, urban renewal, and scientific research, would be a far more prudent investment.

As was so often the case, it was Friedrich Hayek who provided the most comprehensive rebuttal:

“The first part of (Galbraith’s) argument is of course perfectly true: we would not desire any of the amenities of civilization – or even the most primitive culture – if we did not live in a society in which others provide them. The innate wants are probably confined to food, shelter, and sex. All the others we learn to desire because we see others enjoying various things. To say that a desire is not important because it is not innate is to say that the whole cultural achievement of man is not important.”

Throughout the course of his long and storied career, Galbraith would prove a remarkably prolific writer, publishing some 46 books, not merely on economics, but also several novels and memoirs. Still today, his name is often uttered with the same reverence as the undisputed heavyweights of the field, yet no matter Galbraith’s renown among his fellow Keynesians, in truth, the discipline as a whole has largely left his ideas behind. It might even be said that his most lasting contribution to economics exists in terms such as “conventional wisdom”, “age of uncertainty”, and “technocracy’, phrases which Galbraith himself invented and which have since embedded themselves in the language. But of course, even those with little affection for the man once described as “the most famous Canadian America ever produced” overwhelmingly neglect to mention how his legacy endures (and indeed, expands) in the shape of the World Economic Forum.

John Kenneth Galbraith and Klaus Schwab were first introduced sometime in the mid-sixties when both men were at Harvard, Galbraith in the role of a professor, Schwab a student. This meeting had been facilitated, as those who read my last article in this series may already have guessed, by none other than Henry Kissinger. At this time, Galbraith and Kissinger were considered two of the most eminent intellectuals in America, while in addition to their shared membership of the Council on Foreign Relations (an organization which still provokes widescale loathing) they also served on a panel created under the LBJ presidency with the express (albeit softly spoken) goal of re-shaping policy in Europe.

Regrettably, all else is speculation. So thoroughly have Schwab’s Big Tech-affiliated censors purged all mission-compromising information from the mainline internet (or at least buried it in the unsalvageable depths of their search results) that much of his story remains not just unknown, but unknowable. This fact alone should be enough for all reasonable people to question Schwab’s motivations but even this skepticism aside, it hardly seems much of a stretch to suggest that the plans he is now the face of, whether those plans be called the Great Reset, the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Agenda 2030, were first hatched in these seldom-explored corners of American power. There seems little other reason why, in 1971, Galbraith would accompany Schwab to Switzerland and the inaugural meeting of the European Management Symposium, as the World Economic Forum was then referred.

The subject of his lecture has since been lost to the mists of time. In many respects, it is entirely irrelevant. When Galbraith first approached the WEF podium, he was at the height of both his acclaim and his celebrity – his mere presence in Davos lending Schwab’s fledgling project a credibility it would otherwise have lacked. His lyrical dexterity probably didn’t hurt either. Certainly, there could have been few individuals better equipped to articulate, let alone sell, a vision of the future now espoused by Bill Gates, Prince Charles, and Justin Trudeau; by Matt Damon, Bono, and Joe Biden. Fewer still would have possessed an ideology which permitted it, even if it is unlikely, as the applause died down and the Canadian-born economist thanked his audience of bankers and business tycoons, that John Kenneth Galbraith truly comprehended the kind of evil he was about to unleash upon the world.

***As I’ve stated throughout this series, a special note should be made to investigative journalists Michael McKibbon and Johnny Vedmore. It really is no exaggeration to say that a majority of what the world knows about Klaus Schwab they know because of these men - a body of work I hope to add to in part five, when I will profile a man who equipped the WEF founder with a quite uncommon skillset.***

Crypto Donations:

Bitcoin: 1MHzr38VAc3g5cucBGiT8axXkiamSAkEkZ

Ethereum: 0x9c79B04e56Ef1B85f148CaD9F4dBD4285b2f9E69