Wilhelm Reich - The Man who Customized the Normie Mind (Part Three)

That 'diversity' and 'tolerance' are the rallying cries of the society's most intolerant conformists is not merely ironic - it is the wholly intended outcome of decades of psychological manipulation.

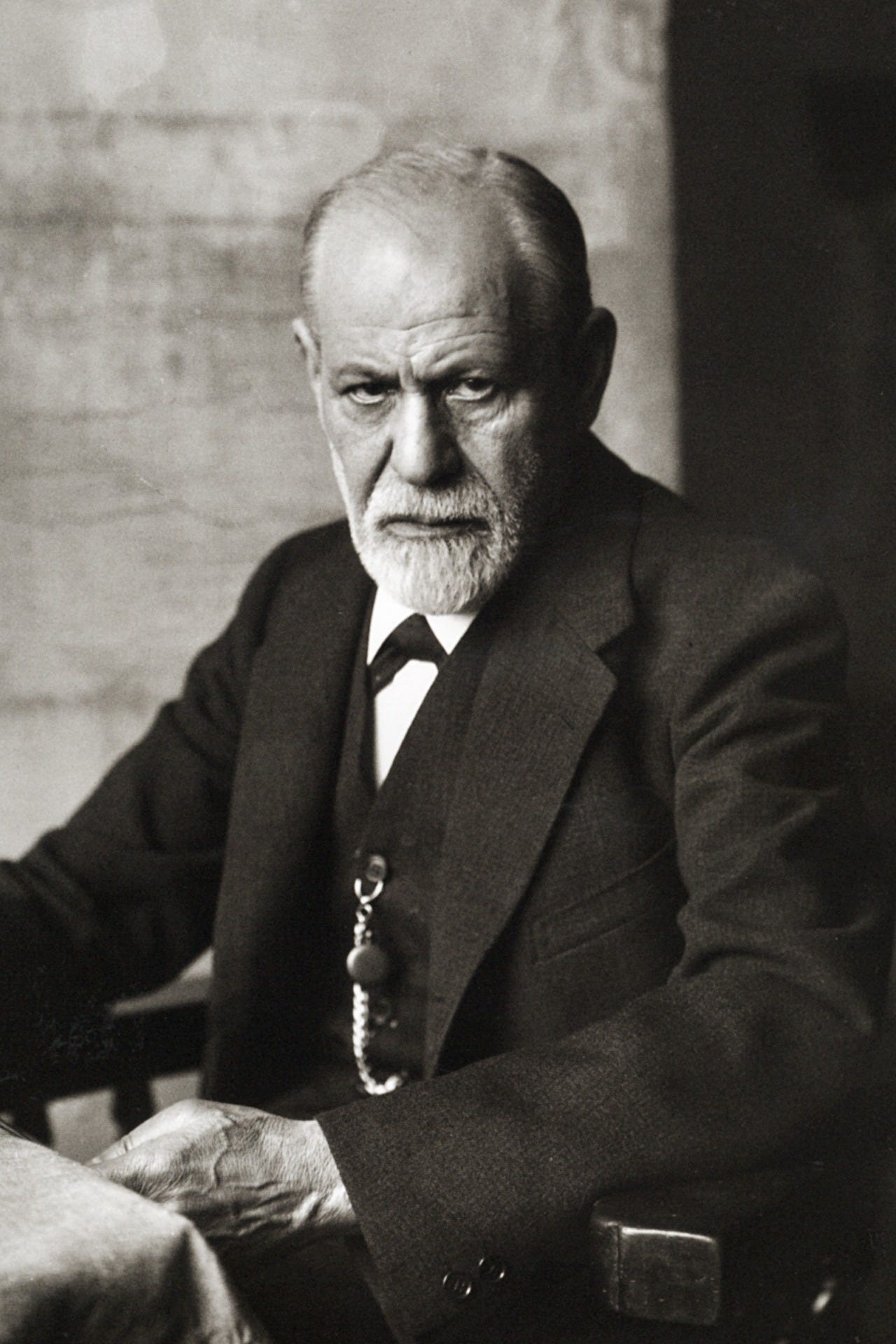

The twin legacies of Sigmund Freud – that as the pioneer of psychoanalysis as well as one of the preeminent figures within the West’s cultural zeitgeist – might well be regarded as complex as they are contradictory. To the layperson, those of us untrained in the technicalities of the human condition, his name and eponymous adjective can be used at one moment as a tool toward deeper introspection and in the next, as a synonym for sexual degeneracy, Freud’s theories shaping everything from art to advertising, poetry to political science, while at the same time remaining so abstract as to appear almost inconsequential.

Within his field of study, his memory is even more dubious. Few who spend their careers wading thorough humanity’s innermost urges now regard Freud’s writings as anything other than fatally flawed, tainted both by mysticism and the prevailing social norms of the age. Yet no matter how thoroughly time exposes these deficiencies, his influence endures, thanks in no small part, to two of his lesser-known relatives.

Regular subscribers of Midnight at the Matinee may remember this article in which I examined the life of Edward Bernays, Freud’s publicist nephew and focus of the first episode of the BBC documentary The Century of the Self. By applying his uncle’s theories initially to business and later to politics, Bernays enabled the most powerful entities in society to manipulate the wider population in previously inconceivable ways, the series’ second instalment profiling Freud’s daughter Anna, who, after the death of her father, fought tirelessly to ensure his ideas remained central to Americans’ concept of mental well-being.

That is not to claim that, even in his pomp, Freud was without his detractors. Arguably the most significant of these was Wilhelm Reich. Onetime protégé of Freud and trusted member of his notoriously cliquish inner circle, Reich’s decisive split with his mentor, as documented in the third episode of The Century of the Self, stemmed from his contention that human unconscious was not the savage, destructive lair Freud imagined it, but rather the dwelling place of natural, libidinous desires only dangerous when corrupted and repressed.

Anna Freud was equally unreceptive to Reich’s ideas as her father. A formidable figure at the head of the International Psychoanalytic Association and staunch ideological opponent of sex, her views could scarcely have differed more dramatically Reich’s, the dispute eroding the pair’s once amiable relationship until eventually Anna kicked him out of the association and into the psychoanalytic wilderness.

It would be a full decade later before Reich’s theories could be rehabilitated. This, after all, was the 1960s and by now most people, primarily the younger generations, had grown wise to the use of Freudian techniques in marketing, regarding them as a sinister and homogenizing force within American society. This distrust of corporations coincided with the slew of left wing political movements which had sprung up in opposition to the Vietnam War, but as these groups’ tactics grew more militant, most notably in the form of the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground, they soon found themselves met with the uncompromising power of the state.

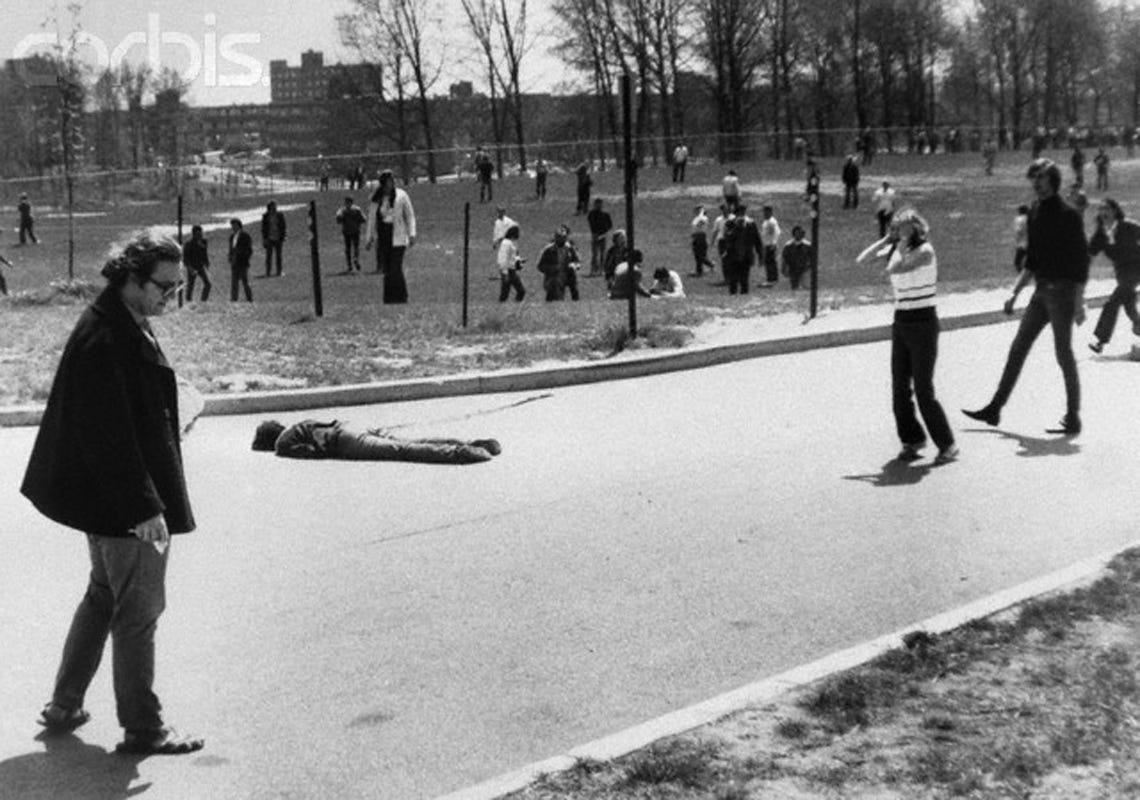

Years of sporadic violence and steadily mounting tensions were to reach a crescendo in 1969, when protests at Kent State University against the expansion of bombing campaigns into Cambodia, resulted in the National Guard shooting four students dead. The event marked both the literal and the symbolic end of the 60s. These legions of anti-war activists – perhaps great in number but nevertheless hopelessly outgunned – were forced to confront the reality that, in the face of such firepower, traditional victory was all but impossible, and so, hoping to change the rules of engagement, turned their attentions inward. It was their belief, fostered by the resurrected teachings of Reich, that a fairer, more just society could achieved if enough people purged themselves of the preconceptions, longings, and taboos that government and corporations had implanted within them – a belief that would soon swell into the Human Potential Movement.

Naturally, as a nationally impactful left wing organization, two issues remained at their core – sex and racism. Their experiments with the latter were to prove particularly disastrous. Throughout their less-than-jauntily titled “confrontation sessions”, groups comprised largely of black nationalists and eager-to-assist white liberals were encouraged to isolate, confront, and thus transcend the issues at the core of America’s racial anxieties. It didn’t work. Most of the black participants resisted researchers’ attempts to dismantle the collective identity from which they derived their power, while the white liberals (being white liberals), were left mentally and emotionally shredded by relentless charges of racism.

Investigations into sex were – depending, of course, on your definition of the word – rather more successful. Granted permission to conduct their studies at Los Angeles’ Convent of the Immaculate Heart, one of the largest nunneries in America, psychoanalysts associated with the Human Potential Movement prompted these usually reserved woman to express themselves in dress, speech, and even sexuality. It was a side of themselves few had ever acknowledged, much less explored, and within six months of the experiment being conducted, half the nuns had left the convent while those that remained had now married their Christian faith with radical lesbian theory.

By now, the 70s had arrived and the values of individualism had reached their peak. Mass production was dead. Not only did the modern consumer expect their purchases to run, cook, cut, unbox, or blend, they also wanted them to make a statement about their own uniqueness and identity.

It was a societal shift which threatened to render Freudian psychoanalysis obsolete as a means of social control, and likely would have done had it not been for a study by the Stanford Research Institute. Using the model devised by Abraham Maslow – Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – interviewers quizzed participants on their most fundamental beliefs, organizing the data not by age, gender, race, or profession as had been done previously, but rather along clearly observable trends in personality.

They called it the “Values and Lifestyles System”.

This system, a precursor to the field of market research, was to offer businesses a higher resolution impression of their customers. No longer did they try to find out how to sell their products. Now, their focus was on finding out what a society of mavericks wanted to buy, advances in technology, particularly the development of the microchip, allowing for near limitless amounts of personalization.

Needless to say, it wasn’t long before the same techniques were employed by politicians. You see, the same culture of nonconformity that had rendered so much of the economy antiquated had also manifested in increased difficulty in getting the population to coalesce around any particular candidate. The solution came from a quite unexpected source. By utilizing the Values and Lifestyles System, political analysts working for the Margret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan campaigns were able to successfully cater their message of deregulation and reduction in the size of government into one likely to resonate with this otherwise unpredictable, individualistically-minded portion of society – a group they dubbed “the inner directives”.

This turnaround was nothing short of remarkable. For a social movement which had sprung out of the left wing uprisings of the 60s and 70s to have manifested in the election of a politician from the right was something few could have foreseen. It was certainly a far cry from anything Wilhelm Reich, the ideological forefather of these movements, had ever envisaged. Although his Marxism was likely a distant second to Anna Freud’s ire in reasons stated for his dismissal from the International Psychoanalytic Association, it was a philosophy which had a lifelong impact on his work, and he would no doubt have been aghast to learn that his teaching had helped precipitate not only a system of free market capitalism, but also the commodity-hungry individualism which helped sustain it.

In essence, the Freudians had won. Although Reich and his followers had briefly threatened to upset psychoanalytic orthodoxy, all they had instead helped to create was the template for a system of social control in which governments and corporations could provoke and ultimately satisfy an infinite number of personal desires – a template that Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, and the rest of the incoming neoliberal order would soon come to ruthlessly exploit.

If you are interested in checking out the rest of The Century of the Self, you can do so right here, while if you prefer, you can always hit the subscribe button below and I’ll be sure to send Part Four of my analysis (along with loads of other great stuff) straight to your inbox.

Crypto Donations:

Bitcoin: 1MHzr38VAc3g5cucBGiT8axXkiamSAkEkZ

Ethereum: 0x9c79B04e56Ef1B85f148CaD9F4dBD4285b2f9E69