On White Altruism and the Origins of Our Suicidal Empathy

“Whoever becomes a lamb will find a wolf to eat him.” - Vilfredo Pareto, Italian engineer, economist, sociologist, and elite theorist (1848–1923)

Up and down the length of the UK, in towns and cities once characterized by their mines, mills, and soot-streaked pubs (and later by their desolate high streets, needle-strewn playgrounds, yet still fastidiously maintained war memorials), a long-suppressed fury is bubbling to the surface. From Epping to Aldershot, Bournemouth to Ballymena—from Manchester, Norwich, and Falkirk to Dover, Cardiff, and Clacton-on-Sea—crowds of ever-increasing size and ever-mounting indignation are taking to the streets in protest at the waves of Third World savagery being inflicted upon their communities. That many of these new arrivals will go on to assault local women is a grim inevitability. The scale of crimes already committed by their predecessors is only now being acknowledged. And yet, while the migrant rape epidemic may have proved the gravest blow to Britain’s once-towering self-conception, even this is but the crowning indignity in a decades-long humiliation ritual perpetrated across the entirety of Europe.

Cowardice, regrettably, has been central to enabling this debasement. Neither can we afford for the roles of apathy, ignorance, complacency, and fatalism to be downplayed. However, so too must we recognize a truth, every bit as shameful, that it was the continent’s near-pathological appetite for altruism which first allowed the barbarian hordes to breach our gates. After all, as both the architects of this invasion and their low-IQ imports well know, Whites, to a degree unique among the races, have been afflicted with an empathy far exceeding the bounds of our tribe—an empathy so ubiquitous, so pervasive, and so foundational to our civilizational psyche, that few even appreciate its presence, much less grasp the depth of its roots.

I. From Survival to Solidarity: Prehistoric Europe and The Birth of Trust

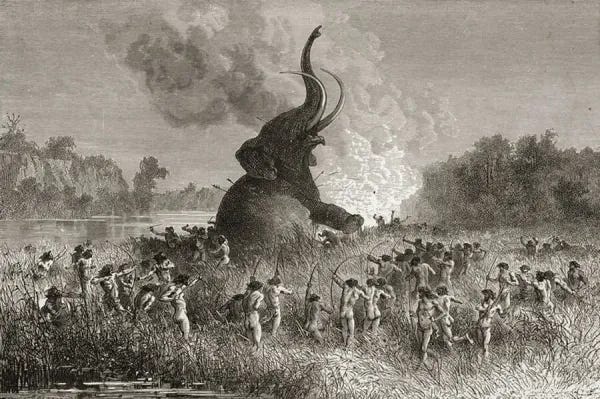

These, it could be contended, stretch all the way into European prehistory, back to the vast steppe-tundras and post-glacial river valleys where our Paleolithic ancestors lived in small, tight-knit bands. Amid such perilous environments, in which a population of only a few tens of thousands lay scattered across an expanse ranging from the Iberian Peninsula to what is today known as the Black Sea, individuals were left little option but to rely on a cooperative approach to survival: resources shared, labor coordinated, and winters prepared for collectively. Over generations, these conditions would select for traits such as reliability and reciprocity over short-term opportunism—conditions that, in turn, helped foster a culture (and indeed a temperament) in which trust extended beyond one’s most immediate kin. As evolutionary psychologist Kevin MacDonald explains:

“Under ecologically adverse circumstances, adaptations are directed more at coping with the physical environment than at competition with other groups… Evolutionary conceptualizations of ethnocentrism emphasize the utility of ethnocentrism in group competition [but this] would be of no importance in combating the physical environment…. These uniquely Western tendencies suggest that reciprocity is deeply ingrained. Within these social forms is a tendency to assume the legitimacy of others’ interests and perspectives in a manner that is foreign to collectivist, despotic social structures characteristic of much of the rest of the world.”

Naturally, this would come to be reflected in family dynamics. In contrast to the cousin-marrying, clan-centric systems that proliferated throughout more temperate, resource-rich regions, the reproductive practices of early Europeans proved advantageous not only from a genetic perspective, but also served to habituate non-relatives into daily collaboration, accelerating the development of interpersonal acumen alongside innovations in hunting, tool-making, and a litany of other advances no one group could have achieved in isolation.

But while such approaches may have enabled our Ice Age forebears to reap both the societal and material benefits of interdependency, so too did they demand a then unprecedented faculty for conflict resolution. Aside from habits of food-sharing, communal childcare, and consensus-based decision-making, inhabitants of ancient Europe, anthropologists assert, also engaged in the far more radical practices of ritualized reconciliation and reparative exchanges, long-term care of the disabled and even rotating access to hunting grounds. This, suffice to say, was a sense of fairness otherwise alien to the primeval world, although it would nonetheless remain many centuries before such tendencies would be cultivated into a coherent, fully articulated moral philosophy.

II. Reason Beyond Blood: Greece, Rome and the Rise of Universalism

As with virtually all Western intellectual traditions, this can be traced back to the fifth century BC and the teachings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—thinkers among the first to recast mankind’s capacity for reason and virtue as a species-wide truism, rather than merely the inherence of one’s tribe. Of course, this was far from absolute. The practical realities of the period, such as they were, necessitated that stark distinctions still be drawn between men and women, citizens and slaves, natives and foreigners, although on a purely theoretical level, it was under their philosophical tutelage that citizens of Greece began conceptualizing themselves, albeit tentatively, beneath the overarching banner of “human.”

Stoicism would crystallize this mindset yet further. For the likes of Zeno, Cleanthes, and Chrysippus (and later Cato, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius), all rational beings participate in the Logos—the principle of order and reason which permeates existence—and are thus bound by (and able to live in accordance with) the single, supreme moral authority. “True law is right reason in agreement with nature,” claimed Cicero, “it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting,” while Epictetus’s cosmopolitanism was more comprehensive still, asking, “If what philosophers say of the kinship of God and men be true, what remains for men but to do as Socrates did: never to answer the name of Athenian, or of Corinthian, but that of a citizen of the universe?”

But though it may have been the Greeks who laid the metaphysical groundwork for notions of cosmic unity and the brotherhood of man, it was not until the Romans that such ideals would be codified into a tangible legal framework. The most explicit example of this came in the form of Jus Gentium, the Law of Nations, which was devised in order to better govern the many “peregrines” or non-citizens brought under their jurisdiction in the aftermath of the three Punic Wars. By proclaiming reason to be the centralmost pillar of its judicial system, what Roman lawmakers effectively established was the earliest civil order which purported to uphold basic humanity as the paramount consideration in justice—an institution essential to binding together its immense and ethnically diverse Empire. As such, most modern historians laud Jus Gentium as a decisive milestone in the evolution of objective legal standards and, by extension, a seismic (and unambiguously positive) shift toward the enduring values of the West. What few choose to mention, however (or perhaps, the consequence they are unwilling to confront), is the innately destabilizing impact this bureaucratization would have, not just upon Rome, but on all subsequent iterations of the European state, in effect, diluting the primacy of blood as the foremost marker of one’s civic identity.

III. The Moralization of Altruism: Christianity and the Reformation

However much Greek philosophy and Roman legislature were to shape Europe’s still fledgling universalism, there can be little doubt that it was the spread of Christianity which saw this elevated to a sacred moral code. Granted, Biblical prescriptions such as “love your neighbor” and “turn the other cheek” are today most often employed by non-believers and liberal denominations as a means to further their own decidedly humanistic crusades. That said, even among adherents of a more fire-and-brimstone persuasion, there can surely be few who would deny that, in the eyes of God, every soul is valuable, and salvation is open to all.

It was this sense of implicit human dignity which compelled early Christians to first identify with the suffering of others and ultimately seek to alleviate it. Hospitals, orphanages, ecclesiastical charities, soup kitchens, and almshouses proliferated throughout Europe in numbers which far surpassed anything prior to the Middle Ages, their work funded by donations offered as acts of solidarity and penance. Eventually, this ethos would be imbued with papal authority in the form of Liber Extra, Gregory IX decreeing the Church—whatever the specific circumstances of their birth—to be a single, unified body. As political philosopher Larry Siedentop notes in Democracy in Europe:

“Christianity took humanity as a species in itself and sought to convert it into a species for itself… It aimed to create a single human society, a society composed, that is, of individuals rather than tribes, clans or castes. The fundamental relationship between the individual and his or her God provides the crucial test, in Christianity, of what really matters. It is, by definition, a test which applies to all equally. Hence the deep individualism of Christianity was simply the reverse side of its universalism. The Christian conception of God became the means of creating the brotherhood of man, of bringing to self-consciousness the human species, by leading each of its members to see him or herself as having, at least potentially, a relationship with the deepest reality…that both required and justified the equal moral standing of all humans.”

The most distilled expression of this was manifested in the Protestant Reformation. With his emphasis on sola fide and sola scriptura (“faith alone” and “scripture alone”), Martin Luther recalibrated Christian focus from cleric-led spiritual mediation toward the believer’s direct accountability before God, with goodwill toward one’s neighbor serving as the external sign of personal devotion. This ethic underpinned much of what Max Weber called the “inner-worldly asceticism” of the Puritans—a form of religious liturgy which advocated disciplined self-restraint in conjunction with an aggressively expansionistic duty of care.

Slavery in particular became a principally Protestant concern. As early as the 1700s, both Quakers and Evangelicals had been at the forefront of abolitionist efforts in Britain, the Netherlands, and the American Colonies, with several high-ranking Calvinist figures already framing slavery as a sin to be eradicated in the name of national redemption. Admittedly, not even the most ardent of these emancipationists ever regarded Blacks (or indeed, any other indentured group) to be their equals in any sense except for the spiritual, and yet, it is not difficult to see how their interpretation of Christ’s all-embracing gospel would set into motion a soon-to-prove powerful engine for race-blind societal reform.

IV. Rational Altruism: Dawn of the Enlightenment

Within the Western civilizational narrative, the Enlightenment is most often remembered, at least insofar as it is remembered at all, as a resolutely secular movement—Europe casting off the shackles of superstition and religious dogma as it burst forth into a triumphant new age of reason and scientific inquiry.

Needless to say, this constitutes but half the story. Whether demonstrated by John Locke’s theory of Natural Rights or the Social Contract presented by Rousseau, Voltaire’s championing of civil liberties or Hume’s unwavering empiricism, at its ideological core, the humanitarian impulses of the Enlightenment can be read as a demystified offshoot of Protestant pluralism, Kant’s Categorical Imperative perhaps the clearest illustration of this throughline. In practice, his declaration that one should “act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” echoes quite conspicuously Jesus’s command to “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” even if his formulation translated Christianity’s Golden Rule into the language of logic and a priori reasoning.

The late 18th Century would see this mantra consecrated as political reality. In the wake of the French and American revolutions, ideals espoused during the Enlightenment would be codified in charters and constitutions which, for the first time, defined national identity in terms of abstract principles rather than ancestral lineage. This was hardly unbounded. In both instances, full citizenship was restricted on the basis of race as well as gender, however, whether granted to native or naturalized White men, this new sense of civic belonging engendered a climate in which tribal loyalties were not merely denigrated as vestiges of a parochial past, but as active impediments to cultural cohesion. Within such a paradigm, there were no natural parameters to the West’s ethical obligations. For many, this circle could and indeed, should be widened indefinitely, Australian philosopher Peter Singer observing:

“Reasoning is inherently expansionist. It seeks universal application. Unless crushed by countervailing forces, each new application will become part of the territory of reasoning bequeathed to future generations. Left to itself, reasoning will develop on a principle similar to biological evolution. For generation after generation, there may be no progress; then suddenly there is a mutation which is better adapted than the ordinary stock, and that mutation establishes itself and becomes the base level for further progress.”

V. From Stewardship to Suicide: Empire, the Liberal Order, and Post‑War Guilt

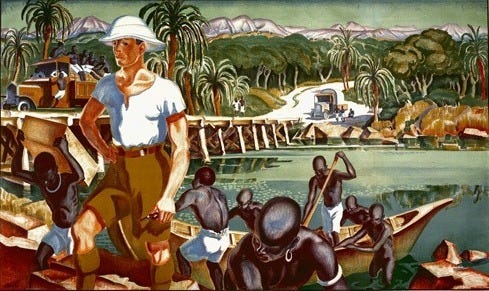

The rise of industrialization (and with it, the re-emergence of empire) would see this “mutation” metastasize into nothing less than a global political project. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, British and French authorities justified their incursions into Africa, Oceania, Indochina, and the subcontinent as a mission civilisatrice—an endeavor grounded in the belief that Western values, institutions, and governance represented the apex of political advancement. Britain in particular pursued what has been referred to as “liberal imperialism”: the spread of free trade, the rule of law, and the imposition of administrative order promoted as the chief objectives of colonial rule. Historian Duncan Bell, on the other hand, offers a more critical depiction:

“Liberal imperialism is usually understood to center on the “civilizing mission,” the idea that liberal states have a right—and, in a strong version of the argument, a duty—to spread “civilization” to the purportedly non-civilized peoples of the world… Societies are arrayed along (and judged according to their position on) a single developmental trajectory, where both the logic and pace of change, as well as the status to be realized, are characterized in terms of “progress.” Although this vision allows for considerable variation within each category, crossing the threshold from “barbarity” to “civilization” is conceived of as a monumental step, one which (depending on the version of the argument employed) will either take an inordinate amount of time given prevailing social and political conditions, or would be impossible without exogenous assistance.”

Yet the same universalist convictions that had once legitimized colonial oversight would be profoundly tested—and, in many ways, fatally undermined—by the convulsions of the twentieth century. The cataclysms of the two world wars would force many within the West to reckon with their most enduring assumptions about the previous age, the Holocaust (or more precisely, how the Holocaust has been memorialized) enshrined as the defining moral parable of the ensuing century. After 1945 and the trials at Nuremberg, ethnonationalism became widely discredited within both political and academic discourse, the rhetoric of cultural purity and racial kinship replaced by the far more humanistic language of the United Nations.

VI. The Atonement Imperative: The West's Self-Immolating Empathy

Against this backdrop, the disintegration of Europe’s longstanding empires was continuing to gather pace. Weakened by conflict, burdened by economic strife, and confronted by rising nationalist sentiments throughout their territories, imperial powers found themselves under mounting pressure, both from abroad and within, to relinquish control over their once-vaunted colonies, their ostensibly paternalistic approach to global governance now regarded, in the eyes of a war-weary populace, as a political liability, if not an ongoing moral failure.

Not that the continent’s ruling elite had any intention of surrendering their influence so readily. Rescripting their role, not as bearers of civilization, but rather as stewards of atonement, bodies such as the UN (and later, NATO), set about appointing themselves purveyors of post-colonial justice—the legacies of conquest, slavery, and segregation now redefined as debts to be repaid through corrective foreign and domestic policies.

The reader likely has little need to be reminded of just how disastrous these policies have proved. Between its ruinous military interventions, hubristic diplomatic entanglements, and, of course, the black hole of financial aid, Europe—as well as the West more broadly—has spent the better part of a century systematically hobbling itself in the name of uplifting those who possess neither the desire nor the capacity to be uplifted. For the most part, it is a role Whites have accepted unquestioningly. Be it a remnant from our evolutionary past, a product of our Christian heritage, or an unholy convergence of Enlightenment ideals and post-colonial guilt, the people of Europe (alongside their Anglosphere cousins) have retained a peerless faculty for altruism even in the face of mockery, cultural desecration, frequent terrorist attacks, and most intolerable of all, the industrial-scale rape of women and children.

But at long last, it would seem that we have reached the limits of what this millennia-entrenched empathy can endure. While it might be the UK where this pushback is most apparent, throughout the Western world—in numbers far greater than the government-corporate hegemon will ever acknowledge—Whites are coming together to articulate, in the only language left available to them, that they are no longer willing to pay for a debt they never incurred. Whether the multicultural Rubicon has already been crossed remains to be seen. What we do know, however, beyond any shadow of doubt, is that neither our megalomaniacal controllers nor their boatloads of Third World footsoldiers have any intention of halting the onslaught. Instead, they will continue to come, in ever greater numbers and with ever greater hostility, until the day comes when at last the White Man, for so long the moral custodian of humanity, finally shakes off the bonds of his compassion and once again remembers how to hate.

Excellent article and very thought provoking! Thank you. I truly believe the English have begun to hate and God help them. My English brothers are ready!

Related: Why the West is NGMI [Part 2]

Self-righteous guilt & victim supremacy

https://sotiris.substack.com/p/why-the-west-is-ngmi-part-2