The Jewish Science: Exploring the Kabbalistic Roots of Modern Psychology (Part One)

“We have stripped all things of their mystery and numinosity; nothing is holy any longer.” - Carl Jung, Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist (1875-1961)

Living as we do in an age of existential dread — a dread precipitated by media-manufactured pandemics and carefully contrived climate crises, “systemic racism” as well as the eminently more plausible prospects of war, economic collapse, and technocratic tyranny — it now seems all but undeniable that the turmoil of our times has taken a ruinous toll on our collective mental health.

The reader has likely witnessed this deterioration firsthand. When once the reality of psychological illness was confined to the occasional troubled soul seen screaming on a city street corner, today, diagnosable disorders represent the defining feature of entire generations, from the legions of depressed young men retreating into isolation to the outbreak of anxiety afflicting their female counterparts; from transgender delusions and a worsening drug epidemic to the veneration of decadence, degeneracy, and wholesale erasure of moral and ethical standards.

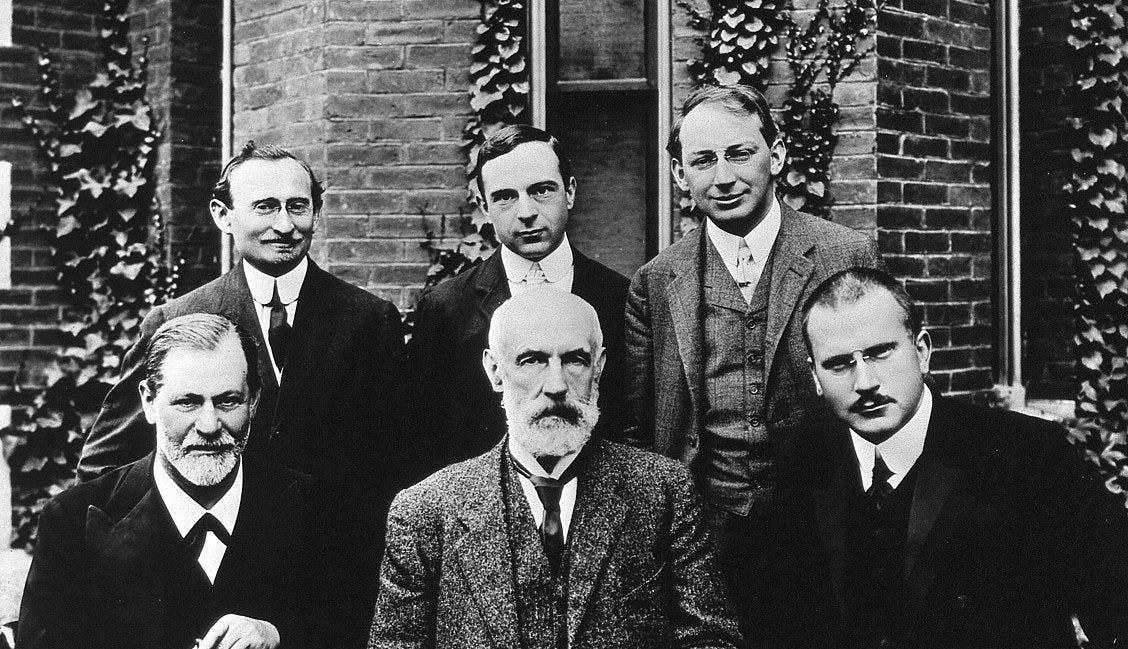

Given this society-wide derangement, it is perhaps unsurprising — some would argue, commendable — that ever-growing segments of the population are pursuing redress for their psychological ills. As of 2024, more than half of all Gen Z and millennial Americans admitted to undergoing some form of therapy, while a great many more have sought solace in the sudden proliferation of mindfulness apps, self-help books, and pseudo-spiritual influencers, all of which encourage adherents, despite their varying new-age veneers, to examine the innermost reaches of the mind — and by extension, the totality of human experience — through a framework first devised by a small but fiercely ambitious group of early 20th-century Jewish intellectuals.

The Roots of Modern Psychology

Although still heralded as one of the crowning achievements of the European Enlightenment, intellectually refined and culturally cosmopolitan, Vienna at the dawn of the 1900s nonetheless faced an uncertain future. Capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire — itself a sprawling, multiethnic patchwork steadily being eroded by nationalist sentiments — the city, conceivably the most diverse on the continent, churned with apprehension and distrust, as Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, and a dozen other semi-assimilated nationalities lived in increasingly uneasy accord. Economic inequality only heightened these tensions. Between the ornate palaces and gilded opera houses, the tree-lined boulevards and marble-clad coffeehouses, the squalor of its slums was seeping rapidly into bourgeois reality, murmurs of revolution exchanged beneath a skyline still pulsing with imposing imperial authority.

This atmosphere, as many literary inhabitants of the time noted, was fundamental in transforming Vienna from a traditionalist stronghold into a petri dish of emerging ideas and new forms of artistic expression. Its musical history is possibly its most renowned. Home to composers such as Brahms, Mahler, and Johann Strauss (and formerly Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven), so too did the city make enormously outsized contributions to the domains of visual art (via the Vienna Secession movement), science and philosophy (through Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle) as well as, of course, politics (Trotsky and Hitler having spent some of their most ideologically formative years there).

Alongside these developments, however, brewed a far stranger force — a movement rooted not in Greek rationalism or the Roman honor code, but instead its practitioners’ near-universal Jewishness.