Prophet, Propagandist or Whistleblower? - Orwell's Troubling Ties to the Fabian Society

"Those in possession of absolute power can not only prophesy and make their prophecies come true, but they can also lie and make their lies come true." - Eric Hoffer, American philosopher (1902-1983)

As humanity continues its slow, stuttering but ever-onward march into its technocratic future – ambling obliviously toward the tripwires of digital IDs, AI-driven surveillance and eventually, carbon-based social credit systems – so too has civilization come to resemble the kind of dystopias that were once confined to the pages of fiction.

These have often proved chilling in their prescience. With western governments’ ongoing assault on free speech and the systematic erasure of their national identities, the book-burning culturicide of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 has seldom felt more tangible. The societal atomization and moral anemia articulated in A Clockwork Orange are now all but endemic to the modern metropolis while even younger readers must recognize, in the open-air prison ghettos of the The Hunger Games, foundations of the 15-minute cities being erected around us – Isaac Asimov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, and Philip K. Dick all penning despotic, dehumanizing depictions of technologies which have since pervaded every facet of our lives.

But while tyranny and the threat of tyranny has always loomed large in literary consciousness, within the wider public debate (and in particular, along the frontlines of social media) it remains George Orwell who epitomizes our collective fear of megalomaniacal authority. I have written before about the enduring relevance of 1984, specifically in relation to the transgender delusion and yet, upon delving into the life of its author, certain realities arise which would seem to undermine Orwell’s legacy as an anti-establishment folk hero – no reality more troubling or more telling than his ties to the British Fabian Society.

What is the Fabian Society?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most charitable answer to this question comes from the organization themselves, their website proclaiming, in conspicuously banal, obscurantist language:

“…The Fabian Society is an independent left-leaning think tank and a democratic membership society. We influence political and public thinking and provide a space for broad and open-minded debate. We publish insight, analysis, and opinion; conduct research and undertake major policy inquiries; convene conferences, speaker meetings and roundtables; and facilitate member debate and activism across the UK.”

This, needless to say, scarcely scratches the surface. After all, today’s Fabians – a coterie comprised of figures such as former president Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer – can trace their ideological lineage as far back as Thomas Davidson, a 19th Century Scottish theologian whose year-and-a-half residence in an Italian monastery would see him immersed in the works of Antonio Rosmini, a priest heralded as one of the earliest pioneers in Social Justice. Imbued with such ideas, the itinerant philosopher returned to England with no less than the intent of "reorganizing human life,” his Fellowship of the New Life established in the hope of doing just that. Among attendees were those of an unequivocally socialistic bent – individuals who subscribed to the fundamental tenants of Davidson’s worldview but who regarded his commitment to volunteerism as fanciful, impractical and rudderless. A brief rift ensued and on January 4th, 1884, nine of these malcontents officially broke from the Fellowship of the New Life in order to conduct what would come to be recognized as the first meeting of the Fabian Society.

Their aims were more expressly political. It was the contention of eugenicists Sidney and Beatrice Webb, dissident sexologist Havelock Ellis, infamous libertine Hubert Bland, alongside the other cofounders, that the state’s most essential function should be to act on behalf of society, a maxim which would translate to progressive taxes, the heavy-handed redress of inequality, and by extension, an all-encompassing welfare system designed to liberate the common man from the shackles of his poverty. Not that they foresaw the common man as having any role in governance, however. This duty would instead fall on an enlightened and benevolent cadre of experts, a moral and intellectual aristocracy who were both committed to and uniquely capable of, the unwavering scientific rationality underpinning the Fabian’s proposed utopia. In other words, themselves.

Mindset and Methodology

Not that this aspiring intelligentsia were under any illusions about how palatable such ideas were within Victorian-era Britain. During their inaugural meeting, before even the fledgling think tank had a name, members were discussing just this problem when author and spiritualist Frank Podmore stood up. Relaying the story of Quintus Fabius, he described how the Roman general had earned the epithet of ‘The Procrastinator’ during the Second Punic War, after a decisive victory at Lake Trasimene had allowed Carthaginian forces to occupy much of the Italian Peninsula – a presence they would maintain for the next seventeen years. Still, Fabius refused to engage. Recognizing the military supremacy of his enemy, Fabius ignored Hannibal’s provocations as well as the near wholesale condemnation from his consuls to instead embark upon a war of attrition, seeking to wear the invaders down through minor skirmishes and continual, low-level harassment. It was through such a gradualist approach, Podmore maintained, that the Fabians (as they would henceforth be known) might one day see their vision of English Socialism become a reality.

Such reticence was not misplaced. At the time, the only significant forces within British politics were the Conservative and Liberal Parties, neither of which offered a viable outlet for Fabian ambitions. Lacking any readymade pathway to Parliament, Webb, Podmore et al. set about engaging England’s disparate network of trade unions and leftist movements, their efforts ultimately culminating in the formation of The Labour Party. But their influence was more than just coordinative. By their own admission, the Fabians regarded themselves as Labour’s “brainworkers” and the “thinking machine of British Socialism,” writing not just the party’s manifestos and policy papers but also its founding constitution, the elitism espoused in the privacy of their gatherings draped publicly in rabble-rousing rhetoric and slogans of working-class solidarity.

Curiously enough, for a movement built so explicitly on duplicity, the Fabians have proved remarkably unguarded in acknowledging their tactics. Shown above is the society’s first coat of arms – a wolf in sheep clothing – a fitting but fatally evocative image since scrapped for reasons of optics. Throughout their history, the group have also marched under the banner of a turtle proclaiming “when I strike, I strike hard,” another allusion to their patient approach to revolution, and yet, arguably the most graphic illustration of their subversive nature remains proudly on display.

Headed by the motto "Remold it nearer to the heart’s desire," the famed Fabian window, designed by renowned Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, depicts its creator, alongside his fellow members, hammering the Earth into a form of their own choosing. Today, the window enjoys a prominent place within the London School of Economics, an institution founded (with the aid of substantial Rothschild funding) by Sidney Webb, Graham Wallas, and other leading Fabians. In conjunction with initiates like Bertrand Russell and John Maynard Keynes, the college has since served as the group’s primary recruitment ground, in effect extending their reach beyond the working class originally courted vis-à-vis The Labour Party, and into the most consequential positions of British society.

Orwell’s Entry into the Corridors of Power

Born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25, 1903, Orwell’s first breath of life, although taken in the shadow of the Himalayan Mountains, was all but turgid with British colonialism, his father Richard stationed in Motihari, India tasked with overseeing the distribution of opium to China. The family were to spend only one further year on the subcontinent before his mother Ida, a cultured and faintly bohemian woman, took Orwell and his older sister Marjorie back to England, raising the children alone until her husband’s eventual return in 1912.

Despite these commitments, Ida’s diary reveals an active and varied social life – a social life, it would seem, which brought her into contact with a number of Fabians. Some of these even boasted ties to the literary establishment and were thus among the first to applaud her son’s early compositions, although it was indisputably Ida’s sister Nellie, herself a suffragette and vitriolic socialist, who did most to foster the young Orwell’s talent, helping not just in a financial sense, but also in forging connections with agents and publishers.

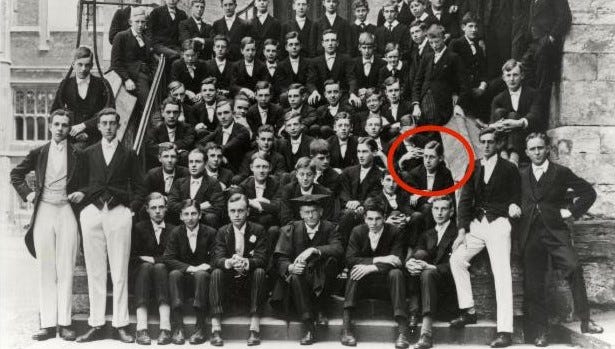

Nevertheless, it was not until 1916 that the budding novelist would find himself ushered into Fabian circles. Founded in 1440 by King Henry VI, Eton College is virtually synonymous with Britain’s ruling elite, producing so many members of parliament that it known as as "the chief nurse of England's statesmen." Orwell did not fit in. Self-described as “lower upper middle class,” gaining entry to the school only via a scholarship, his subsequent writings characterize his time at Eton as one of resentment, loneliness, and cruel, sadistic bullying, yet for all his apparent isolation, Orwell did manage to meet at least one acquaintance who would become a lifelong friend – a French teacher by the name of Aldous Huxley.

Huxley’s own membership of the Fabian Society began during his time at Oxford, the author acknowledging it as far back as his first published piece of fiction, The Farcical History of Richard Greenow. It was quite natural that his life would follow such a trajectory. After all, the Huxleys constituted nothing less than an intellectual dynasty, Aldous bonded, either by blood or by marriage, to a litany of distinguished scientists, philosophers, artists and educators – his grandfather Thomas Henry so instrumental in propagating Evolutionary Theory that he became known as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” This represented the foundational text on which the family was raised, Huxley’s brother Julian, himself a Fabian, going on to head both UNESCO and the British Eugenics Society, in addition to cofounding the World Wide Fund for Nature. His vision of progress was unambiguous:

“Consider the problem of over-population. Rapidly mounting human numbers are pressing ever more heavily on natural resources. What is to be done?... We are given two choices -- famine, pestilence and war on the one hand, birth control on the other. Most of us choose birth control.”

There is presumably no need to remind the reader of the analogies with Aldous’s work. Many may even contend that A Brave New World predicts even more astutely than does 1984, the kind of technocratic caste system we find ourselves slipping into, Huxley’s fictional citizenry anesthetized to the meaningless of their existence, as we are increasingly anesthetized to ours, by a cocktail of entertainment, promiscuity, and drugs. Given the author’s lineage, it hardly seems a stretch to conclude that these insights were not purely the product of creative prognostication, but more so an intimate foreknowledge of the future he and his relatives were actively attempting to precipitate.

Orwell’s Socialism

It is testament to both the enduring impact of 1984 as well as the essential truths it contains that today, it is often those quoting the novel most enthusiastically who prove most surprised – at times even aggrieved – to learn of its author’s lifelong commitment to socialism. In actuality, such sympathies were evident as early as his first political book, The Road to Wigan Pier. Documenting his two-month journey through England’s northern mining towns, Orwell describes in vivid sordidness, a Britain quite at odd with his regular London literary circles – the outer reaches of the country emaciated by poverty, benighted by class prejudice, and suffused with a squalor that at once kindled his sense of injustice and offended his bourgeois sensibilities.

To his credit, Orwell was no hand-wringing class tourist. In 1936, following the outbreak of civil war in Spain, he immediately enlisted in the P.O.U.M - a semi-independent Trotskyist faction within a broader coalition fighting to repel Franco’s forces. As he notes in Homage to Catalonia, the weeks prior to deployment were the first time the author had seen his egalitarian ideals made manifest, saying of his time in Barcelona:

“There is a sense in which it would be true to say that one was experiencing a foretaste of Socialism, by which I mean that the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism. Many of the normal motives of civilized life—snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc.—had simply ceased to exist. The ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England; there was no one there except the peasants and ourselves, and no one owned anyone else as his master.”

For now, Orwell had no policy prescriptions of his own, merely pages of observations and evocative, eloquent outrage. It was not until 1941 and the publication of The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius that these were to finally take shape.

At the core of the book lies the assertion that a uniquely English brand of socialism would arise, this iteration of the ideology distinguished not by a desire to tear up the country by its roots, but rather a willingness to build upon the quintessential trappings of Britishness. Seemingly incompatible institutions such the Monarchy would survive, so too a free press and Christian values, while the Empire, which at the time still spanned a quarter of the planet, might be rebranded as “a federation of Socialist states.” These “antagonisms,” as Orwell called them, would calm the populace even as society was being rebuilt around them, showing “a power of assimilating the past which will shock foreign observers and sometimes make them doubt whether any revolution has happened.” It was a vision, it seems superfluous to say, which found considerable favor among the Fabians.

Fabians and the Literary Elite

Right from their very inception, the society had endeavored to use literature in general, and fiction in particular, as a means of disseminating their doctrine. Although George Bernard Shaw is widely remembered as a dramatist of near peerless wit and penetrating social critique, conceivably the most important playwright since Shakespeare, his work remains inextricable from leftist dogma, Widower’s House and Mrs. Warren's Profession perhaps the most demonstrative examples. His politics were far less circumspect than Orwell’s. A vocal supporter of both Stalin and Stalinism, alternatingly denying, defending and celebrating atrocities committed by the USSR, Shaw’s convictions might be said to fall somewhere been “proudly misanthropic” and “nakedly Malthusian,” the ideological basis of which is best delineated in his play Man and Superman, a work that borrows as much from Darwin's theory of evolution as it does Nietzsche’s notion of the Ubermensch.

Unquestionably the Fabian’s most prolific wordsmith, however, was H.G. Wells. The author of over a hundred books, his literary corpus – still today the bedrock of science fiction – gave rise to just about every trope within the dystopian genre, whether it be the social stratification of The Time Machine, the scientific dictatorship in The Shape of Things to Come or the primitive transhumanism practiced on The Island of Dr. Moreau – themes of selective breeding, inescapable surveillance, and cradle-to-grave indoctrination pervasive throughout his work. Wells’ 1940 publication New World Order, even served as the basis for the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights while his most brazenly Fabian-inspired treatise, A Modern Utopia, portrays a parallel Earth freed from the limiting tribalisms of nationality and religion, its integrated and fluid population governed, just as the writer and his radical cohorts envisaged, by a wise and ethically upright order of “voluntary nobility.”

Orwell the Propagandist

While it exceeds the scope of any one article to dissect the motivations behind each component part of the Fabians’ literary output, what remains clear is that, contrary to his present-day persona, there were occasions Orwell likewise felt it permissible to manipulate public opinion via the written word. When interviewed for a job at the BBC’s Eastern Service, he indicated the absolute “need for propaganda to be directed by the government," stressing that during wartime – and presumably, crises more broadly – objectives must be pursued without squeamishness or misguided loyalty to the truth. His broadcasts to India, designed to counter German efforts at undermining imperial links, were unabashedly agenda-driven yet his connections to Britain’s PR apparatus ran deeper still. The Ministry of Truth, where 1984’s doomed protagonist Winston Smith performs his own reality-rewriting duties, was in fact modeled after the country’s Ministry of Information, a building Orwell was well-acquainted with, given his wife Eileen’s role in its censorship department.

In Orwell’s defense, he left the BBC after just two years, heartily disgusted by what he’d seen there. This habit of joining institutions only to become quickly disillusioned by their inner workings had long been a pattern for the self-professed idealist. His youthful involvement in the Burmese Police had been fundamental to igniting Orwell’s disdain for the British Empire while his months spent volunteering in Spain only solidified his suspicion that leftist causes were doomed to in-fighting. So too would the author cling to his collectivist principles even as he grew more contemptuous of those who endorsed them, deriding upper-crust socialists as “left-wing secret teetotalers with vegetarian leanings” who alienated the working class in favor of “the fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist.”

Many who earned his ire were, not unexpectedly, card-carrying Fabians. But Orwell’s antipathy went beyond a basic misalignment of personalities. In 2003, after some fifty years of secrecy, the British government released a list compiled by the author in which he identified 135 left-wing writers and artists as potential "Soviet sympathizers." This he supplied to the British Information Research Department, a secret branch of the Foreign Office operating during the Cold War, earmarking for further scrutiny, Fabians such as novelist Naomi Mitchison, journalist Kingsley Martin, archaeologist V. Gordon Childe and even George Bernard Shaw himself.

Orwell: A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

This would certainly lend credence to the claim that Orwell’s masterwork was written, at least in part, as a direct attack on the Fabians, warning of the tyranny which would inevitably ensue if ever they were to realize their objectives. This, while undeniably speculative, is not without merit. Although the official story behind the book’s title asserts that Orwell, upon advice from his agent, simply swapped the last two digits of the year his manuscript was completed, it has also been suggested that the name was a thinly veiled reference to the society, 1984 marking their centennial anniversary. Further inferential evidence lies in the date of Winston’s first diary entry, April 4th, a day which falls exactly one hundred years since the publication of the Fabians’ original pamphlet.

Naturally, all this begs the question, if Orwell really did wish to expose their intentions, deriving his fictional hellscape from the blueprints he’d heard discussed behind the closed doors of their meetings, then why did he not categorically call out the Fabians by name?

Well, perhaps he did.

Upon the death of the author’s second wife, Sonia – a woman he married just months before succumbing to tuberculosis – the organization acquired (and then promptly sealed) the entirety of Orwell’s archives, representatives of publishing behemoth HarperCollins stating that the group will maintain the copyright of 1984 until later this year.

By then, of course, regardless of what these documents reveal, it will likely be too late to exorcise the poison from the wound. Following the UK’s most recent elections, a total of 141 Fabians took their seats in parliament, Keir Starmer ostensibly the most senior. In his little more than six months as Prime Minister, the Labour leader has succeeded in accelerating the already rapid overhaul of British life – importing wave upon wave of third-world migrants, running interference for their crimes, and pompously imprisoning citizens who might voice objection. But even he is merely an administrator. Further up the Fabians’ totem pole of power is Sadiq Khan, the long-standing Mayor of London also chairing the C40 Climate Leadership Group, a body charged with implementing the 15-minute city initiative. More ominous still is Tony Blair, a WEF collaborator and unapologetic war criminal whose steadfast support for open borders and mass vaccinations, digital IDs and net zero self-immolation has rendered him a living, breathing avatar for globalist aspirations.

Today, these individuals and countless others like them, sit at the helm of a vast and secretive empire. 140 years since the Fabian Society was formed, this current crop of operatives at last possess the power and the capacity, after generations of careful infiltration, to plunge mankind into the centrally-planned, algorithmically-guarded prison system first conceived by their predecessors. Theirs is a future, if ever it materializes, defined by conformity and all-pervasive fear, bereft of both humanity and the hope for anything better – a future that was most accurately articulated, whether as cautionary tale or confessional, by esteemed author, avowed socialist, and enigmatic member of the Fabian Society, George Orwell.

Great article well researched and cogent

Should be required reading for senior members of Reform UK

Bravo! Just an excellent example of why I love the Stack!